On a cold October night in Chicago, Javier Collina searched for shelter after traveling for six weeks by foot, bus, truck, and train from Colombia to the United States. Collina fled Venezuela earlier in 2022 due to the unlivable situation in Venezuela fueled by an economic crisis. The economic inflation fluctuated and even reached as high as 65,000% in 2018, according to the BTI transformation index.

“I couldn’t feed my family when I lived in Venezuela or Colombia,” Collina said.

Collina was initially turned away from the Salvation Army Freedom Center in Humboldt Park, one of nine shelters paid for by the City of Chicago and managed by the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS). Staff at the shelter told him they were full.

“I will sleep on the floor,” Collina pleaded. So, he did.

Collina is one of 3,854 Venezuelan asylum seekers to arrive in Chicago since Aug. 31, as reported by DFSS. Those fleeing Venezuela are part of the second-largest migration crisis in the world, according to the United Nations.

Inadequate communication between city and state officials fell on the shoulders of asylum seekers searching for work and a new life. Abrupt and unannounced changes to shelter locations within the Chicago area and unseen indoor shelter conditions reveal a sanctuary city with an unsustainable long-term plan.

A comprehensive plan is necessary to provide for these migrants, said 25th Ward Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez. “[The City and State] are coordinating efforts without disclosing what is really going on in these locations,” he said.

The Reverberation of No Communication

In late August, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott bussed Venezuelan asylum seekers from Texas to sanctuary cities such as New York City, Washington, D.C., and Chicago. This was without any notice to Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Gov. J.B. Pritzker.

Lightfoot and Pritzker publicly welcomed the migrants, per Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance, and condemned the unannounced and disorderly decision by Abbott.

“The other states may be treating them as pawns; here in Illinois, we are treating them as people,” Pritzker said in a speech he gave on Sept. 14.

During a Committee on Budget and Government Operations meeting on Oct. 15, DFSS Commissioner Brandie Knazze said the department is applying for a $16 million grant to support Chicago’s nonprofits for migrants. This grant would come from a $150 million Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) food and shelter grant.

The City of Chicago set aside a $5 million contingency fund to cover costs associated with Venezuelan asylum seekers. It’s unclear how much has actually been spent between Aug. 31 and Dec. 1, according to Rose Tibayan, the director of public affairs, at Chicago’s Office of Budget Management.

After the asylum seekers arrived at Chicago Union Station, the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) coordinated health screenings at intake centers. After a few days at intake centers, the asylum seekers were relocated to either hotels in suburbs under the state’s jurisdiction or shelters in the city managed by DFSS, Marisa Kollias, spokesperson for IDHS, said.

In early September, Burr Ridge Mayor Gary Grasso found that Pritzker sent dozens of asylum seekers to the Hampton Inn hotel in his suburb without any warning. Similarly, Elk Grove Mayor Craig Johnson was unaware of the decision to house asylum seekers at La Quinta Inn in his village, according to the Elk Grove newsletter, in September.

“We can empathize with these refugees and want to help them, but we cannot do that effectively unless we properly communicate,” wrote Grasso.

The asylum seekers lived in Burr Ridge for 11 days before moving again to another location, according to a Burr Ridge Village press release.

The La Quinta Hotel in Elk Grove is a two-hour train ride Northwest of downtown Chicago.

“I directly asked the mayor’s office and state representatives if I could visit the shelters to verify the conditions that the refugees are under. Not once was I given the opportunity to see these facilities,” said Sigcho-Lopez.

The Unsustainable Process

The Chicago Mexican American center Little Village Community Council (LVCC) aims to serve the community through social services. The placement of asylum seekers in the suburbs was nonsensical, LVCC President Baltazar Enriquez said.

“The mayor put them as far as possible, [away from] Latinx neighborhoods like Little Village, Back of the Yards, or Pilsen,” said Enriquez.

Yorvi Rivas, an asylum seeker from Venezuela, was in a shelter in Chicago’s West Ridge neighborhood and accessed free legal assistance and a CityKey. He found these resources through northside city nonprofit Centro Romero.

CityKey is a government ID that has benefits, including transit passes and discounts from business partners and prescription drugs. Since August, the Chicago City Clerk has printed 9,000 CityKeys that help Chicago residents, including asylum seekers, according to the Office of the City Clerk.

However, CityKeys are not available to asylum-seekers placed in the ten state-sponsored suburbs.

Hidden Conditions Within

Rivas resides in a makeshift shelter that was once a public library. The shelter accommodates over 100 asylum seekers and lacks basic necessities, said Rivas.

“We have the option of using a shower at another location, but it can take up to an hour to travel to and from; so I just don’t shower,” Rivas said.

Sigcho-Lopez and Enriquez said they encountered challenges trying to check the conditions within city and state shelters. Sigcho-Lopez visited a shelter in Harvey after not receiving any response from officials.

“What I saw was shameful,” said Sigcho-Lopez.

The children at this shelter were not able to go outside, he said. Sigcho-Lopez also heard reports of drug use inside the shelter. The asylum seekers at the shelter have since been relocated to Bridgeport.

City shelter placement is also unreliable. Rivas said he has been moved 15 times.

The Salvation Army, where Collina stayed, addresses emergency homelessness, drug addiction, rehabilitation and other social welfare programs, according to the organization’s official website.

“They aren’t helping them find jobs, and they are not interested in these people,” Enriquez said. “[It] has become like a little jail.”

The Salvation Army and DFSS declined to be interviewed about the conditions within the shelters.

They Are Here to Work

“They [Venezuelan asylum seekers] want to work,” said Immigration Legal Assistant Frank Sandoval with the Spanish Community Center, a United Way nonprofit agency. “That’s why they are here.”

Delmar Janampa and his wife, Nairubi Janampa, were sent to the Holiday Inn near the Chicago O’Hare International Airport on Oct. 4, nearly two months after the family left South America on foot. Nairobi Janampa interviewed to work as a cleaning person at a hair salon a few blocks from the hotel.

Yorvi stood outside a Home Depot near his shelter with a sign that said, “I am looking for a job,” and found a painting job that lasted only a few weeks.

Collina had no legal help in applying to seek asylum since arriving in Chicago. He is working at a restaurant under the table, meaning he receives payment in cash and isn’t registered in the employer’s payroll.

Janampases, Collina, Yorvi have one year to apply for asylum since entering the United States, according to Sandoval.

“What usually happens is that asylum seekers come by themselves, and they fend for themselves,” said Helena Olea, a human rights lawyer at Alianza Americas, a network of migrant-led organizations.

Eduardo Caceres translated interviews for Collina and Yorvi, and Johan Gotera translated for the Janampases.

Sidebar

Between 2014 and 2020, the Venezuelan economy shrank by two-thirds due to failed social policy, spurring a humanitarian crisis causing 9.3 million Venezuelans to go hungry, according to Human Rights Watch.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro committed human rights violations ranging from the persecution of political opponents, to attacks on demonstrators, and killings in low-income communities, according to Human Rights Watch.

Maduro rose to power in 2014 and maintained it through censorship, repression, and electoral manipulation. In 2018, Maduro was reelected despite the condemnation of an unfair election. Throughout the last eight years, 7.1 million Venezuelans, 25 percent of the country, have fled to neighboring countries such as Colombia and Peru, according to the United Nations.

In May, Title 42, which prohibited migrants from entering the country out of

concern for the spread of contagious diseases, was terminated. This allowed thousands of Venezuelan and other South American asylum-seekers to enter the country for the first time since the start of the pandemic.

Two ways of obtaining legal work authorization are possible in the U.S. One way is by applying for Temporary Protective Status. The alternative is to apply for asylum. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) decides both asylum and TPS cases.

According to the data-clearing organization at Syracuse University, only 7.2% of the 3,720 asylum seekers who arrived in Chicago in September and October applied for asylum.

The asylum application process can take anywhere from six to nine months and require a professional to help navigate, said immigration legal assistant Frank Sandoval.

Temporary Protective Status is available to Venezuelans due to the severe humanitarian crisis in Venezuela. On July 11, USCIS extended TPS for Venezuelans by 18 months. The extension is in effect from Sept. 10, 2022 to March 20, 2024.

Between January 2021 and Oct. 21, 237,000 Venezuelans attempted to enter the U.S. In September, 34,000 Venezuelans entered Texas, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Since December of last year, New York City has received 32,000 migrants from Texas, more than eight times the amount than Chicago. Washington D.C. received a total of 8,400 Venezuelan asylum seekers since September of last year.

New York Mayor Eric Adams declared a state of emergency on Oct. 7. Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul has employed 147 members of the New York National Guard.

Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser requested help and was rejected twice by the National Guard. The D.C. Attorney General Karl A. Racine stated $150,000 designated funds as grants to six local groups for expenses related to housing, clothing, and transportation, according to a Sept. 1 press release.

Thousands of asylum seekers ended up in the shelter system. NYC opened an 84,000-square-foot tent camp on Randall’s Island, according to the New York Times on Oct. 22.

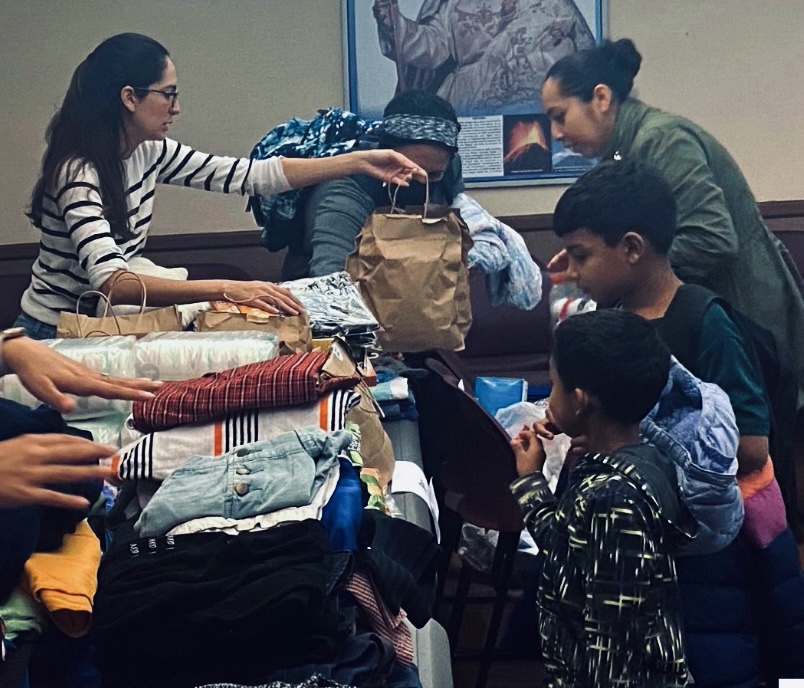

Cover Photo: Volunteers help migrants bused from Texas to Washington, D.C. endure their first winter. Credit: Danna Matheus

Kala Hunter is an environmental journalist passionate about climate change mitigation and environmental justice. Kala writes about regenerative food systems, endangered species, and urban forestry. She is currently earning her Masters in Journalism at Northwestern University.

Chelsea Zhao is a graduate student of health, science and environment journalism at Northwestern University. Her previous work appeared in Cicero Independiente, Southside Weekly, and the Caregiving magazine. She is passionate about topics of environmental racism, climate change and sustainability.

Publisher’s Note: Illinois Latino News is dedicated to covering the social determinants of health. A social determinant of health approach has seldom been applied to immigration. A report in Annual Reviews finds that global patterns of morbidity and mortality follow inequities rooted in societal, political, and economic conditions produced and reproduced by social structures, policies, and institutions. The lack of dialogue between these two profoundly related phenomena—social determinants of health and immigration—has resulted in missed opportunities for public health research, practice, and policy work.

Part of Illinois Latino News’ (ILLN) mission is to provide mentoring and real work experiences to students. ILLN also amplifies the work of others in providing voice and visibility to the Hispanic-Latino community. ILLN is grateful to collaborate with schools of higher education like Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications in fulfilling that commitment.