Fifteen-year-old Ileana Salinas — vibrant, outgoing and set on going to college — found herself in an entirely new country with a new educational system after fleeing Mexico City in 2004.

She remembers taking her first academic placement exam alone, in an empty classroom. The results labeled her as not proficient in English.

Salinas is among the thousands of immigrants in Arizona — many of them Latino children — placed into a “structured English immersion” program, commonly known as “English-only.” Students are separated from their peers for hours to learn the language in an English-only environment. For Salinas, this meant time away from her math, science and other classes critical to academic success and college readiness.

“I was rushing to try to get out of (English-only) classes, so I could fit in regular English,” she said, adding that like many native English-speaking students at the time, she also needed regular English course credits to graduate.

Arizona is the only state with English-only legislation still in effect. Under the state’s laws and policies, children who aren’t proficient in English are segregated at school for hours at a time from their peers whose primary language is English.

Though many of Arizona’s GOP political leadership, including State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne, are staunchly committed to enforcing its K-12 English-only program, the state has one of the lowest English learner high school graduation rates in the country, at 55%. That’s 22% lower than the state’s overall graduation rate — according to the U.S. Department of Education’s latest analysis of 2020 data.

In the two decades since voters approved the ballot measure that mandates an English-only education learning model, many Latino and immigrant students have struggled academically. Experts say these restrictions negatively affect English learners’ postsecondary educational outcomes, particularly the state’s substantial population of Spanish-speaking Latino children.

A dual or multi-language model is the best way for children who don’t speak English to learn and become college-ready, many students, educators and scholars say. In the years since Horne previously held office in 2011, Arizona leaders have worked to incorporate limited versions of these models alongside English-only instruction to better educate all students, as well as strengthen the state’s future and economy. Still, Horne — after his 2022 election — has moved to reignite his fight against nationally-recognized bilingual and multilingual education programs.

He has sued Arizona schools, the governor and other state leaders who stand in the way of his crusade for English-only education.

For Salinas, Arizona’s school system was difficult to navigate, particularly without support from her parents, who didn’t realize college was an option.

“They thought, you’re undocumented, you can’t go to college,” she said. “It wasn’t that they didn’t believe in me, it’s just that they didn’t know that it was possible.”

The classroom separation in Arizona only exacerbated her sense of isolation.

Currently, students in English-only programs spend two to four hour blocks in classrooms learning the language, limiting their time to take other classes and often physically isolating them from their English-speaking peers.

“I definitely did feel disconnected when I’d go to my other classes, I’d feel like the different one. Like the one that didn’t know enough,” Salinas said.

Numerous studies over the past four decades have shown that an English-only approach hinders academic performance and students’ long-term success, including equitable access to higher education.

“It’s terrible. It’s the worst thing you could do to kids. It really truly is,” said Virginia Collier in an interview with Arizona Luminaria. Collier is a professor emerita of bilingual, multicultural and English as a second language education at George Mason University. “Structured English immersion is very inefficient and very ineffective in the long term.”

Collier and her husband, Wayne Thomas, have spent their careers developing educational models for English language learners and evaluating their long-term success. Thomas is a professor emeritus at the graduate school of education at George Mason University. Their research shows forcing students to learn English before they’re able to learn other key academic subjects permanently delays their education.

Findings like these have prompted other states, like California, to ditch their “English-only” policies in favor of dual language programs in which students learn subjects in their native tongue and English in the same classes as their English-speaking peers.

The California Department of Education said there is “comparable or higher achievement of students in dual language programs as compared to students in English-only programs,” an assertion backed by scholars including Thomas and Collier.

“There are several studies that have shown that the kids who have graduated from a dual language program are outperforming (peers in non dual-language programs) in college,” Collier said.

Salinas believes spending her first year learning only in English prevented her from excelling in her other academic subjects.

“I feel if I was able to learn many of the subjects in my language, I could have advanced very fast while I was learning English,” she told Arizona Luminaria in Spanish.

Salinas’ grades were the highest in math, which she described as a language that she had already started learning in school in México.

In 2000, Arizonans voted for Proposition 203, an initiative that mandated an “English-only” educational model for English-learning students. At the time, Arizona had the fourth highest percentage of Spanish speakers in the nation but English learners’ academic performance was lagging.

The proposal said “the public schools of Arizona currently do an inadequate job of educating immigrant children, wasting financial resources on costly experimental language programs whose failure over the past two decades is demonstrated by the current high drop-out rates and low English literacy levels of many immigrant children.”

Ultimately, Prop. 203 mandated that children learning English spend four hours a day separated from their peers to attend English immersion classes, limiting their academic options and potential.

Students learning English under Arizona’s isolation models continue to underperform with consistently low test scores. Since at least 2018, no more than 14% of English language learners were deemed “proficient” in English in state accountability data. The Legislature loosened the state’s bilingual education laws in 2019, allowing for more flexibility in how English is taught. Now, schools have the choice to reduce the hours of mandated English instruction from four to two a day.

Horne, the state’s superintendent, has been using legal means to push back on non English-only curriculums since the start of his latest four-year term in 2023 and he’s already campaigning for reelection.

One of Horne’s first moves as superintendent was to sue schools not using structured English immersion, arguing that it violated Prop. 203, the English-only statute. The case made it to Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Katherine Cooper who dismissed the lawsuit last spring, ruling that Horne did not have discretion over approved teaching models that are overseen by the State Board of Education and that he had no standing to sue in his current role.

In a press release following the judge’s ruling, Horne said “the districts that opposed our position will regret this development” and warned of further legal action.

Horne made good on his threat.

Most recently, Horne supported a lawsuit filed by his wife, lawyer Carmen Chenal Horne, on behalf of a parent of a child in the Scottsdale Unified School District against Creighton Elementary School District in Phoenix.

Unlike the Scottsdale district where 82% of the student body is White, more than half of Creighton’s students identify as Hispanic or Latino and live in households that earn a median income that’s less than two thirds that of Scottsdale, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Additionally, Creighton district has students who speak 28 languages and in 2023 tested almost double the amount of children for English proficiency than in Scottsdale.

The lawsuit alleged that Creighton district’s dual language programs violate Prop. 203’s mandate that children learning English are taught only in English. The office of Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes has filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Horne has maintained his advocacy for an English-only approach to bilingual education since his first term as state superintendent in 2003. He cites one particular 2006 study by Joseph Guzman, who he appointed to an associate superintendent role in January 2023, as the foundation for his support of restricting students from learning academics in their native and new language. Horne published a report in late October 2023 he said proves a dual language model is inferior.

Thomas and Collier argue that while English immersion may show improvements in the short term, success is fleeting.

“The wheels come off, the bottom falls out, and nothing good happens with English-only after a couple of years,” Thomas said.

After those first years, Collier said, English-only students fall significantly behind academically compared with their English-speaking peers. “That means that they’re scoring at about the 20th percentile,” she said of their reading scores.

“There’s no way they can get into college,” she said.

Thomas and Collier conducted a seminal five-year study in the early 2000s of elementary and middle school students in a dual language program at an Oregon school district. The study outlined the high effectiveness of dual language instruction in closing the educational gap between children learning English and native English speakers.

They found that English learners in the third grade tested at a 14.93 point gap in reading scores compared with native English speakers. However, that gap closed to 4.94 points within four years. Students learning English in the Oregon dual language program were on track to “completely close the gap within two more years,” they reported.

Conversely, in Arizona, students in the state’s English-only program continue to show deep educational equity gaps compared with their native English-speaking peers. Only 3% of eighth grade students with limited English proficiency in the state are prepared to be successful in high school math and only 5% of third graders with limited English proficiency passed their reading exams — the lowest rates of any subgroup, including students who are homeless or economically disadvantaged in the state, according to a report on 2022 data by the Center for the Future of Arizona.

Thomas and Collier pointed to multiple research papers which show that a dual language approach involving English and non-English speakers learning alongside each other in both languages is the most effective learning model.

The nonprofit All In Education issues an annual report on the state of Latino education, power and influence in Arizona and found deep disparities among students’ educational rights.

“This is especially true for our Spanish speaking community as state leaders prioritize attacks on English Learners and limit their options to choose high quality programs, like dual language,” according to the 2023-24 report by the nonprofit group working to ensure communities most impacted by education inequities are the ones making decisions. “Leaders who refuse to accept the talent and potential of a community that is bilingual and bicultural are limiting Arizona’s economic prosperity and ability to compete in a global economy.”

Now, with Horne back in charge of Arizona schools, some teachers and administrators fear that hostility against dual or multi-language education has risen again in the form of lawsuits and other threats.

Cause for alarm, some educators say, dates back to past civil rights investigations into how the state’s department of education treated student English learners.

In an interview with Arizona Luminaria, Horne said this criticism stems from ideology and English speakers’ desire for more dual language programs.

“I know that the supporters of dual language are very emotional,” he said.

An investigation by the U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights office and U.S. Department of Justice found that from 2006 to 2010 the Arizona Department of Education — then under Horne’s leadership — discriminated against student English learners based on their nationality. The report determined that Arizona also was violating federal laws that require educational agencies in the U.S. to “overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by students” in course studies, according to a 2012 resolution agreement to address the alleged bias.

While the state’s Department of Education disagreed with the findings, they implemented changes to their reclassification methodology, or how they determine a student’s English proficiency based on their Arizona English Language Learner Assessment, commonly known as the AZELLA test.

Since then, reclassification rates, the percentage of students who test out of English-only programs, have dropped dramatically, according to data kept by the Arizona Department of Education. Horne blames the poor implementation of the structured English immersion model.

“After I left office, things deteriorated,” he said.

Horne holds that reclassification rates were the highest while he was superintendent from 2003 to 2011.

“I implemented structured English immersion, and equally important, undertook intensive training for the teachers as to how to do it, and then we got it (reclassification rates) up to 31% in three or four years,” he said.

But these numbers are dubious. The Arizona Auditor General found the data during Horne’s tenure untrustworthy in a 2011 audit of the state’s Arizona English Language Learner Program, saying “because data is either unavailable or unreliable, the effect of SEI models is unknown.”

Not all of Arizona’s schools follow the English-only model. In the Tucson Unified School District, bilingual schools that predate Prop. 203 are used to working around the state’s ever-shifting policies. The largest district in the Tucson area, TUSD, has dual language programs at 12 schools.

Patricia Sandoval-Taylor, the district’s language acquisition department director, said there are 105 different languages spoken across the district’s student population. The diverse student body is reflected in the colorful knick knacks and cultural trinkets that adorn her office and desk.

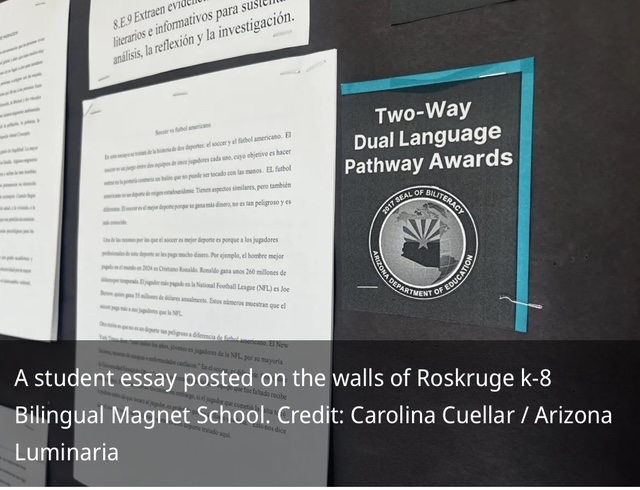

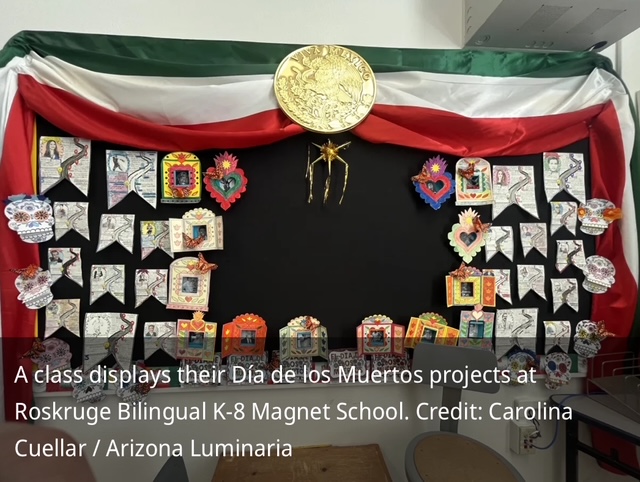

Roskruge Bilingual Magnet K-8 School has had bilingual instruction since 1987. The building is old and the halls are vibrant with clusters of student projects, accolades and murals lining the walls. One student’s idea for an assignment to create and name a new constellation — “El Pantalones de Drake” — is illustrated on bright yellow construction paper and represents the cultural and language fusion permeating every classroom.

The primarily Mexican-American student body includes generations of students that have sent their kids or currently work there.

While the district still has English-only instruction for students who don’t qualify for a waiver or don’t want to be in a dual language program, Sandoval-Taylor said they see the most success with their dual language program students.

The program incorporates college-readiness components by requiring Advanced Placement College classes in the curriculum.

“You could actually leave high school with already enough credits for a minor in Spanish. And that’s just from retaining and mastering your native language,” Sandoval-Taylor said.

She said graduation and proficiency trends are going up, but the Arizona English Language Learner Assessment keeps changing and external factors like the pandemic have made it difficult to look at comparable data.

Even then, recent proficiency improvements on the assessment test statewide are marginal with only a 3% increase. In the 2022-23 school year proficiency was 12% compared with 9% in 2021-22.

“In math, and in English language arts, they are surpassing their mainstream kiddos … the same cohorts that they’re with within their school,” Sandoval-Taylor said.

While dual language programs are successful, they can also be challenging, she said. With so many languages spoken across the district’s student population, it’s impossible to have bilingual educational support for each of them.

Because of this, she said, it’s important to retain a limited and student-focused form of structured English immersion programs.

Salinas ultimately reached her goal of attending college — studying psychology and Spanish literature at Arizona State University. She said this wouldn’t have been possible without support from organizations outside Arizona’s English-only education system. This includes the Aguila Youth Leadership Institute, a program that helps students transition into college and connect their cultural heritage to personal, academic and professional success.

Salinas’ desire to study psychology was largely influenced by her experience as a non English-speaker.

“Moving here made me be very aware of human behavior. Because I couldn’t really understand English as much, I was just observing a lot and it made me realize, ‘Wow, there are different ways of living and different ways of seeing life,’” she said.

She said her journey to college was a struggle and she feels her English Language Learner classes didn’t help prepare or get her to college.

“If anything it kind of put me behind a little bit because I needed to get out of the program to have enough credits to graduate,” she said.

Today, Salinas manages Aliento’s Cultiva program that creates spaces for youth, mixed-status families and immigrant community members to express and heal through bilingual workshops or events like art sessions, group therapy and open mics. Through her job and personal hardships, she sees the impact of Arizona’s educational policies on students and their resolve.

“It is very important that we have the leadership in the educational system to revise all of these policies and assessments,” she said. “I see a lot of students who are just tired and so dismotivated because they just see so many barriers and hurdles that they just kind of want to give up.”

Salinas no longer feels the intense insecurity that stemmed from being pulled into a separate class and fearing her classmates would make fun of her accent. But when she enters a classroom, she sees her younger self reflected in the students.

Now, when she speaks, she alternates between languages, her voice and smile growing whenever she speaks in her native tongue.

“To be honest, every time I can speak with someone bilingual or someone who speaks Spanish, it brings me comfort,” she said in Spanish.

Publisher’s Notes: This story was originally published by Arizona Luminaria.

This story is a collaboration between Arizona Luminaria and Open Campus, and produced with support from Ascendium Education Group and the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program. Open Campus is a nonprofit news organization partnering with local newsrooms to deliver expert coverage of higher ed.