Bad Bunny is everywhere, from Spotify’s top charts to sold-out stadiums that pulse like heartbeats. The pride that emanates from la isla de Puerto Rico, with its native son is palpable. The ownership every Puerto Rican, from the island to the diaspora, feels at this moment —over their culture, their identity —is hard to understate.

This sense of belonging and pride is something I explore in my new book, Sentido: Finding Sense and Purpose in Design Leadership. Part memoir, part guide, it reflects on what it means to be Puerto Rican, Nuyorican, and multiethnic — and how that layered identity shapes the way I understand connection, purpose, and presence.

But pride alone doesn’t tell the whole story. What often gets lost in translation for those unfamiliar with Puerto Rico’s history is that the island Bad Bunny represents still grapples with colonial neglect, gentrification, and economic erasure. Much of his music speaks to this, amplifies it, and refuses to let it be ignored. Debí Tirar Más Fotos (“I Should Have Taken More Photos”) is a love letter to the Puerto Rico that was and the Puerto Rico that must remain, just as No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí (“I Don’t Want to Leave Here”) holds the ache of wanting to stay home even when home is under threat.

This is the paradox of visibility and invisibility, of existing within systems designed to erase you.

Puerto Rico’s story is one of complexity and contradiction, a place that holds both joy and grief in equal measure. Like many Spanish words that resist direct translation, uniquely Puerto Rican phrases like La Brega capture that tension perfectly. “The struggle” can be one of joy or of pain; often, it is both.

In Sentido, I write about El Yunque, Puerto Rico’s rainforest, as a living system that resists extraction by regenerating from within. After Hurricane María and near-total devastation, the forest reorganized itself. Roots deepened, and new growth emerged from fallen trunks — nature’s way of remembering. Bad Bunny’s work mirrors that instinct. He turns the spectacle inward, redirecting attention from global fame to local truth. Like El Yunque and the people of Puerto Rico, his art reminds us that the power is in the people. Community and culture endure. Regeneration itself becomes a form of resistance.

Once known as Borikén, home to the Taíno people, the island was claimed by Spain in 1493 and later traded to the United States after the Spanish–American War. Citizenship came in 1917, but not sovereignty.

Puerto Ricans could be drafted to fight wars abroad yet could not vote for the leaders who sent them. The Jones Act still dictates how and from where goods arrive, and how much they cost. The island became a “Commonwealth” in name only: its economy remade to serve others, its flag once outlawed, its people asked to adapt rather than belong.

Colonialism didn’t end; it changed form. Policies like Acts 20 and 22 invite outsiders to profit while locals are priced out of their own neighborhoods. Austerity boards overrule elected officials. After Hurricane María, aid arrived slowly, revealing what power looks like when it decides who is worth saving. And yet, Puerto Rico persists, creating, gathering, remembering. That duality of presence within erasure continues to define it.

In Bad Bunny’s music video for El Apagón (“The Blackout”), there’s a deliberate bait and switch. What begins as a celebration, a pulsing anthem of pride and presence, transforms into a documentary, a love letter, and a warning. It isn’t just about power outages; it’s about power itself, who holds it, who profits from it, and who is left in the dark.

Leadership, as it shows up through Bad Bunny, isn’t hierarchy. It is a shift from power over to the power of projection, a reorientation toward compassion and interdependence. Sharing, not hoarding, resources and thriving. Thriving despite circumstance. His artistry is not extractive but regenerative. It centers community, redistributes power, and creates space for others to grow. Like El Yunque, he reminds us that endurance is not about standing tall, but staying rooted, grounded.

Just as he hosted a three-month residency in San Juan (with the first 30 shows reserved solely for Puerto Rican residents) to infuse the local economy, on the last night, the eighth anniversary of Hurricane Maria, he hosted “una mas,” the finale event that marked the start of a multi-year partnership between Bad Bunny and Amazon aimed at supporting Puerto Rico through initiatives in education, economic development via a “comPRa Local” storefront, and agriculture.

Y ahora. As we prepare to hear him take the Super Bowl stage — and perhaps learn a little more Spanish in the process — Puerto Ricans are once again navigating duality: the pride of global recognition alongside the reality of living in an America that still questions our belonging. The forced removal of our language, the fear of racial profiling, the erasure that persists, all while one of our own stands in full Boricua glory before the world.

To see Benito on the world’s largest stage, performing entirely in Spanish, is a declaration that we don’t have to translate ourselves to be understood. His presence is not assimilation but assertion, a reminder that Puerto Rican identity is not conditional or dependent on mainland recognition. It isn’t something to be performed for approval; it’s lived, embodied, and enduring. In that moment, with the island reflected on the global stage, Benito reminds us that visibility without purpose is vanity, and visibility with integrity is power. For Puerto Rico, that power is not new. It has always been there, steady and alive, pulsing quietly beneath the noise, waiting.

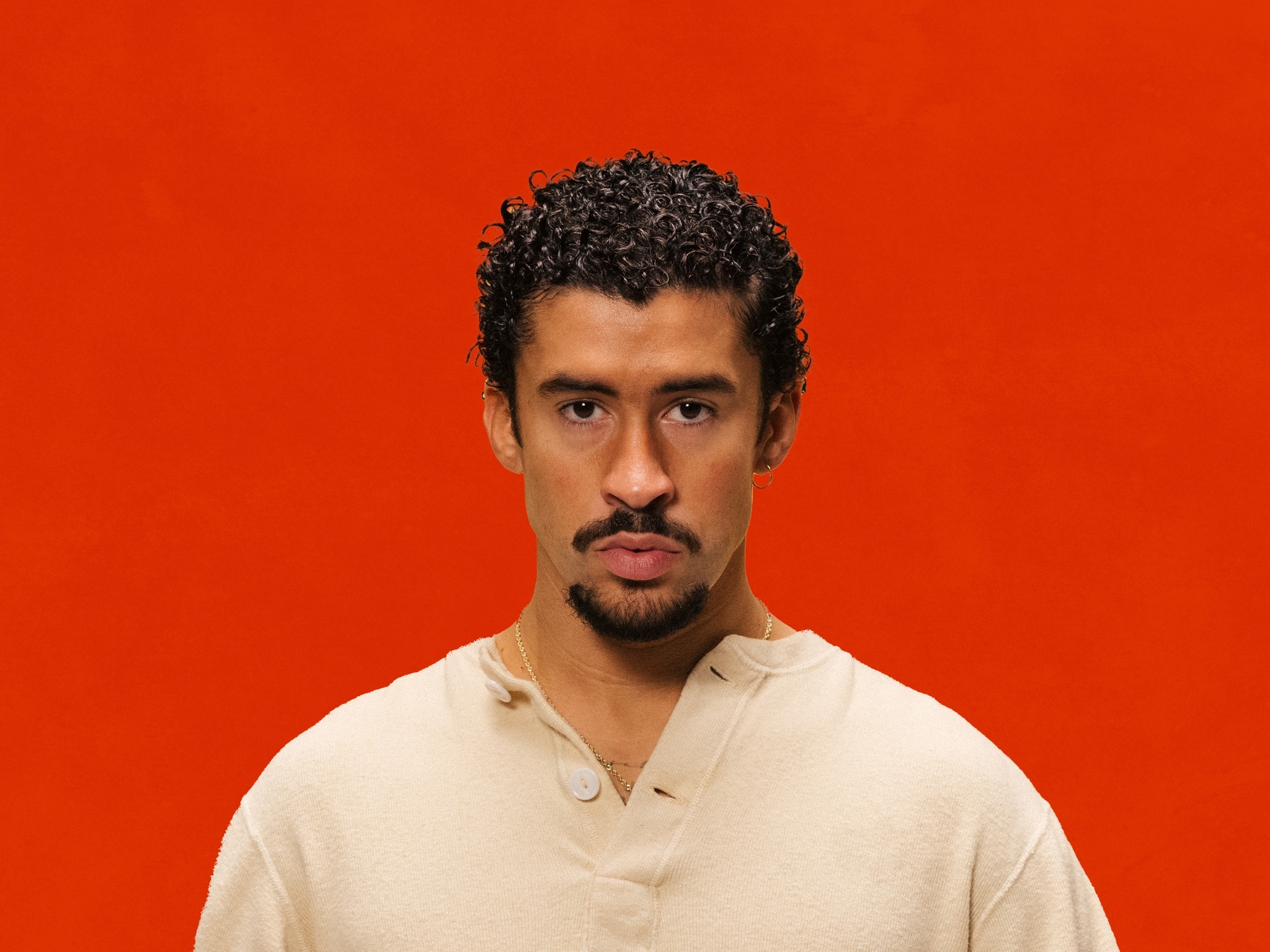

Alison Rand is a strategic design expert, consultant, thought leader, and writer with a passion for promoting more inclusive operational systems. A born-and-raised New Yorker, Alison’s worldview was shaped from an early age by her multi-ethnic upbringing and exposure to diverse backgrounds and ideas.

This October saw the debut of Alison’s first book, Sentido: Finding Sense and Purpose in Design Leadership, which serves as both a memoir and professional guidebook.

If you have an idea for an Opinion-Editorial piece, please send your ideas to Info@LatinoNewsNetwork.com for consideration.