For six years, Dr. Stephanie L. Canizales listened to the coming-of-age stories of unaccompanied migrant youth inside of Los Angeles’ church courtyards, community gardens, English night classes, McDonald’s restaurant booths and more.

“Story after story… as much as there was pain and suffering, there was resilience and hope,” Canizales said.

Her first book, ‘Sin Padres, Ni Papeles’ compassionately weaves the voices of Central American and Mexican immigrant youth who struggled to adjust to life in the United States after migrating without parents nor papers.

“It’s both a story about inclusion but also deep marginalization,” Canizales said.

Nearly 129,000 unaccompanied minors crossed the U.S. Southern border in 2022, according to The Department of Health and Human Services. Though it became widely reported in 2014, when a surge in immigration exposed the public to photos of detained children in cages.

Canizales’s research began in 2012, when the Barack Obama administration passed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which allowed some immigrant youth temporary relief from deportation and renewable legal work authorization.

Though DACA had positive impacts on some, it left out 62 percent of the undocumented youth who did not meet the policy’s educational requirements, Canizales wrote.

Among those left out were the youth that she met in L.A., many of which because they did not travel with a legal guardian or documents, took on the role of low-wage worker instead of student.

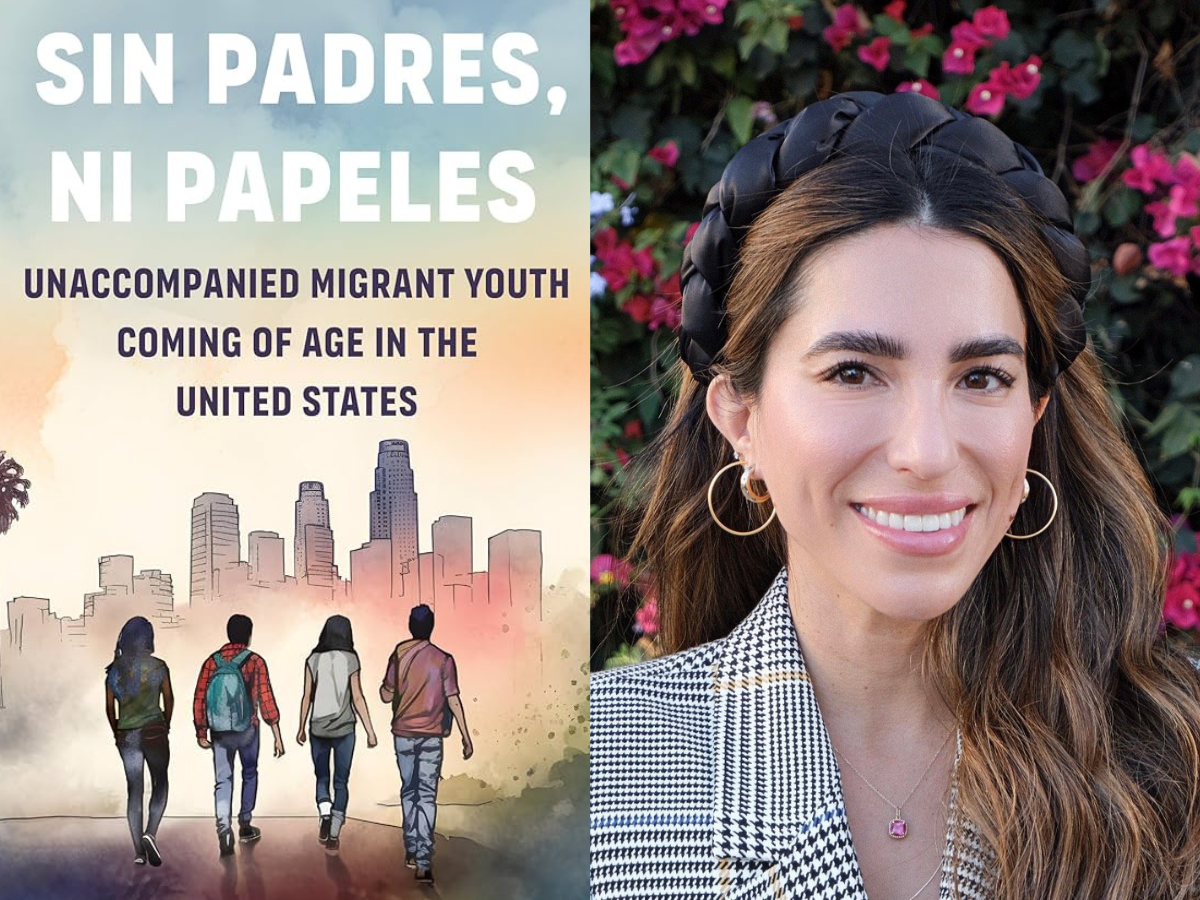

Dr. Stephanie L. Canizales, is a researcher, author, and professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Photo: Provided by Nanda Dyssou

The book cover of “Ni Padres, Ni Papeles.”

Photo: University of California Press

Canizales gently probes at the hearts of youth like Tomás, a garment worker who left Guatemala at 14-years-old a few years after his mother abandoned him and his older sister Susana.

Susana was the first to leave Guatemala and initially welcomed her younger brother to her Pico-Union home where her undocumented husband and U.S. born children had settled.

But Susana soon kicked Tomás out because she was afraid he would place her family at higher risk of deportation, leaving the young boy emotionally callused with no one to turn to for support.

“Tomás’s only social connection was to his employer, who allowed him to sleep in the factory until he found a room to rent in an apartment with other young garment workers,” Canizales wrote.

Many unaccompanied youth like Tomás struggled to find community which led some down the path of what Canizales described as perdición or perdition.

This is when youth fall into drugs, get into unhealthy relationships, commit self-harm and more.

“These things are not failings on young people’s part … or immigrants are not inherently destined to do these things,” Canizales stressed. “What I really try to highlight is that anyone without meaningful social ties would fall into these circumstances as a way of coping with the loneliness.”

Despite experiencing hardships, youth would often portray on social media that they are “doing better” in the U.S. than they actually were which “perpetuates the idea of the American Dream,” Canizales said.

“There is an attempt to save face with the families and communities they’ve left behind,” Canizales said. “They send the best stories of success at work, they send as much as they can in financial remittances and don’t tell families that they are left with five dollars.”

On the other hand, when youth do form close relationships, they are more likely to experience adaptación.

“There are cases where young people can become materially adapted to what it means to be a worker, or how to use public transit or where to go for groceries,” Canizales said.

Moreover, Canizales said that while writing the book she wanted to “critique the top-down markers of success that we’ve imposed, not just [on] immigrant groups, but [on] society at large.”

Frequently the “success” of “a good immigrant” is measured by socioeconomic markers, such as if they earn a college degree or start a business, Canizales said.

“You are looking at a group of kids who are completely dislocated from childhood, from parent-led households, from K-12 schools, from the U.S. legal system, for indigenous youth, from the Latino category but also just in a society that is both anti-black and anti-indigenous, and anti-immigrant,” Canizales said. “All of these compounded, there was never a chance in heaven on earth or in hell that these young people would be able to accomplish those things because they are just so far from the normative.”

Instead Canizales said she ended all of her interviews by asking the youth what success meant to them.

“Young people said, ‘Success to me is I can sow faster, I learned some skills, I speak a little bit better English, I went from being a dishwasher to a busser, to a server,’ Canizales said. “In that same vein, it was always measuring their emotional selves by those metrics. ‘I was abused in my home country, I was really depressed when I got here, me sentia disorientado and now look at me, I don’t feel as depressed.”

Canizales said she was continuously “shocked” while hearing the stories of youth throughout her 6 six years of research.

“I’m listening to people talk about, now a decades-long experience that they were not anticipating, that has been very painful for them,” Canizales said. “But they still hope that tomorrow will be better.”