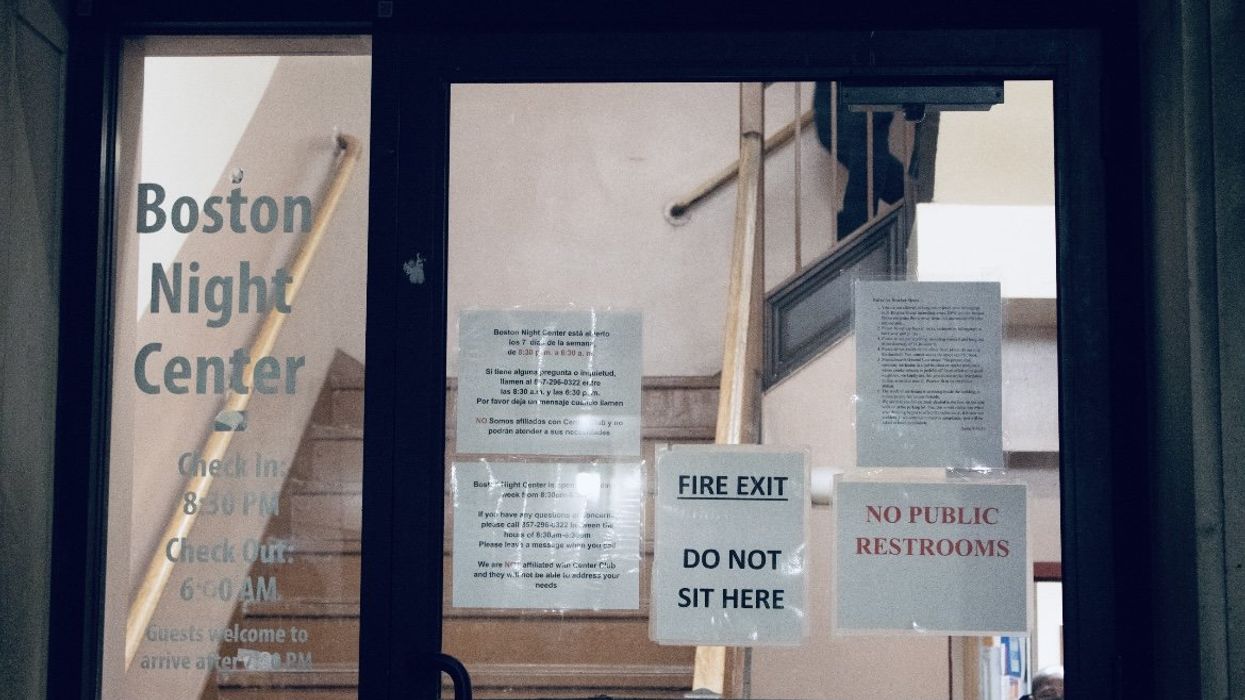

In front of the Boston Night Center at 2 p.m., a line snakes along, its head marked by a green sleeping bag. A pedestrian straying one street too far from the main road might do a double take, wondering if the lime-colored lump is filled with clothing or a person. Yet this line is held not by people, but by things. Bags of all shapes and sizes sit out in daylight on the sidewalk, as if daring someone: Yeah, come on, steal from people experiencing homelessness.

The shelter system in Boston is a beast, consisting of both governmental and nongovernmental support for migrants and unhoused Americans who fall into a myriad of categories. While living in the same space, even sometimes in the same room, migrants and unhoused Americans receive different governmental treatment and support, causing a dissonance in perceptions of the other. Each group faces unique roadblocks and avenues for assistance. Yet one thing is clear: the crisis is real, and the needs are overwhelming. As icy air hits the city, this intensity only heightens.

Massachusetts is the only right-to-shelter state in the United States, a designation that legally obligates the state to provide shelter to families and individuals in need. This policy has made the state a destination for migrants and unhoused Americans seeking assistance, placing unique pressure on its shelter system. Boston has the second-highest rate of homelessness among major U.S. cities, according to a 2024 report by Boston Indicators. Yet the city also stands out with one of the lowest rates of unsheltered homelessness, ranking eighth nationwide.

Only 6% of Boston’s homeless population is unsheltered, starkly contrasting the national average of 40%. This difference highlights local policies’ effectiveness and underscores the immense challenge of meeting rising demand. As the number of families and individuals seeking assistance grows, the strain on state resources intensifies, testing the limits of what even a right-to-shelter system can provide.

Since its state of emergency announcement in 2023, capping the shelter capacity at 7,500 families or 24,000 individuals, Gov. Maura Healey has rolled out many new policies to tackle the overflow. Many of these include prioritization systems for shelter placement and stay limits. Healey has also continued urging the federal government to act more on immigration reform to help manage the influx.

Rise and shine and shut the doors is at 6:30 a.m. From there, yawning residents of the Boston Night Center head off in different directions. Some go to aid centers around Boston, some to work—authorized and unauthorized—and many to the St. Francis day shelter down the street to escape the encroaching Boston cold and have something to eat in the sleepy, fluorescent cafeteria space.

The doors reopen at 8:30 p.m., yet the line begins long before reprieve from the cold. There are 55 tickets handed out each night. No ticket, no entry. Thus, the bags holding spots.

Many government emergency shelters have strict rules and regulations, while nongovernmental ones have more leeway. Run by Bay Cove Human Services, the Boston Night Center on 31 Bowker St. is just a few minutes’ walk from the Government Center station. One just needs to show up—no identification or signing is needed. Unlike most shelters in Boston, men and women sleep together, making it an attractive choice for couples.

The Boston Night Shelter, located near Government Center station, offers anonymity, requiring no personal information for a night’s stay—a draw for many unhoused individuals.”Shandra Back

As owners reunite with their belongings in the late afternoon, the sun vanishes, revealing the icy undertone of Boston’s air. In the summer months, dusk barely kisses the concrete before the doors open. Now, darkness falls four hours before opening time.

The routine is not new. Many sleep in the Boston Night Center night after night for months, yet the teeth-chattering and shivers remain unrelenting.

“In my country, it’s the Caribbean,” says German Garcia. “Imagine, hot land, hot land. This is crazy here for me.”

Garcia stands out on the darkening street like a traffic cone—literally. As the lights flick on, they bounce off his reflective orange jacket. Dangling from his neck are a pair of white wired headphones, their port waiting for a connection. A subtle bouncing swagger and sturdy, slim build place him in his 30s, yet the silver atop his head brings this into question.

He speaks with respect, yet as he explains his journey through one country, two, three, and four, an imploring tone bursts out, and his arm movements follow suit.

Traversing from his home in Caracas, Venezuela, through many borders, the Darien Gap, and the perilous Mexican freight train known as “La Bestia,” he says. “I don’t know if you’ve heard of it,” he explains, noting he had to ride it twice. His first two times, he was turned back at the border. On his third attempt in May 2023 in El Paso, Texas, he made it in.

In Missouri, the pay was too low; New York was too crowded, and the process time for migrant support was painfully slow. When he heard that Boston was a sanctuary city helping migrants, he didn’t think twice. From Venezuela to Boston, he travels alone. “There are also a lot of bad people, a lot of evil along that whole route,” he says. “You also see so many things… so many ugly things.”

The ugliness didn’t stop when he reached Boston. His first roof was the Pine Street Inn. At the largest homeless shelter in New England, “hay de todo,” he says—”there’s everything.”

He’s not a man who needs much; after his journey, he feels he can appreciate a lot from a little. Yet this place is horrible, he says. Some people violate, they steal, he says. But the worst by far is the bathroom. He says men were trying to see him naked. Eventually, to defend himself, he raised his fists and was shown the door for a month.

Yet even when his 30-day suspension was up, he vowed not to return. For the last five months, the Boston Night Shelter has been his home. It’s less comfortable, he says. There are no beds. But it’s a worthy price to pay to undress without raising a fist.

But the murmurings of migrant support in Boston turned out to be true. Once a taxi driver in Venezuela, Garcia is now studying to take his license test to become a chauffeur or Uber driver in the city.

As darkness intensifies, Garcia returns to his place in line, ready for a fluorescent heat that won’t fill the yearning for home but will at least thaw him from the cold he never expects to get used to.

By 7 p.m., the sidewalk is packed to the curb. Some people are chatting and joking; others, are leaning and silent. The line shows many faces. Various communities convene each night behind the walls of the shelter—migrants and Americans alike.

While grateful for the resources Massachusetts offers to the unhoused, Garcia feels frustration at some homeless Americans, whom he believes are not fully utilizing those resources to better their situations. In Venezuela, there are no resources like this, he says.

“That’s why I get so angry with these people who don’t want to recover,” he says, speaking about addiction. Each day, Garcia goes out and works to improve his life situation, he says. “And these people? Look, no, no, they don’t take advantage.”

A few spaces behind Garcia, leaning against the brick wall, is Andrew G. He was the first to get in line this afternoon, and his shivers increase as night encroaches slowly over the alley.

His quiet eyes peer out from the parking lot as he leans on a long metal bar, using it as a bench. In a red puffer jacket and brown leather shoes, he’s sporting business attire on the bottom and casual on top.

Andrew, 23, was raised in Long Beach, California. He says he ran away from home after high school, having endured abuse from elementary through high school. First coming to New York, he stayed with a few friends but soon got into trouble with one friend’s landlord. This led to a period of couch surfing and unstable living situations in New York for about three years.

From New York, much like Garcia, Andrew heard murmurings of Boston’s government assistance benefits and better opportunities for the unhoused. With nowhere else to go, he came.

Since arriving in Boston in early 2022, shelters have been his main home. Yet each night in tight, enclosed places, with curfews and rules about coming and going, he must confront the trauma of his abuse while suffering from claustrophobia.

Due to increasing panic attacks, he begged his housing caseworkers to tell him all the documentation he needed to gather to apply for housing assistance.

Now, after two years in the process, Andrew is signing a lease in December to move into his own apartment in Quincy. The rent is heavily subsidized by a voucher program through the Boston mayor’s office.

Yet until he has a room to himself, he still shares one with 54 other people. It used to be around 40, he says, but the numbers keep creeping up.

Upon entering the door of the home he hopes soon never to return to, he’s patted down for weapons and sent downstairs to leave his bags for the night. Anyone with yoga mats or sleeping bags is allowed to bring them up to the main room.

He describes the place as both quiet and joyful. Night after night, he says the food brought in is always the same revolving menu of spaghetti or rice with meat. He’s not the only one who’s sick of it. Yet, those with food stamps will sometimes order in and share a pizza or another treat.

Eventually, the dark room is filled with snores and the occasional gust of wind. The lights come on at 5 a.m., and by 6:30 a.m., everyone is out.

Caseworkers have been working with shelters to help homeless Americans rehouse for decades. Yet, as migrant numbers continue to increase, the Massachusetts government is now getting resettlement agencies involved.

Jessica Cirone, the director of community engagement at the International Institute of New England (IINE), is involved in a new pilot program that complements the existing shelter system.

This pilot program, launched in March 2022, contracts IINE and other resettlement agencies to rehouse 400 migrant families living in Massachusetts emergency shelters. IINE specifically has a goal of rehousing 50 of those families over the course of the year-long contract.

Since the pilot began, Cirone says, as of November, about 23 families have been resettled, and they hope to have another 10 to 15 by the end of the year. The start has been slow because this work was unprecedented, and the bureaucracy and creation of a whole new department proved more difficult than expected. In an ideal world, the process of moving someone out of the shelter after identifying the apartment would take three weeks at most.

Three weeks maximum. Andrew shakes his head. “Migrants get housed automatically, while we as American citizens would be out here freezing in the cold waiting,” he says.

Three years. That’s how long the average subsidized housing wait time in Boston is, according to the Public Health Post: an all-time high. “They’re getting more special treatment than us,” says Andrew.

“Tickets! Tickets!” calls out a Bay Cove employee managing the shelter’s door, who requested anonymity due to the nonprofit’s media policies. The doors aren’t supposed to open until later, but as nights get colder and darker, the staff opens earlier.

People who stayed the night before can automatically receive a ticket for the following night. Then there are six tickets reserved for people who work, he explains. Two are for people coming from another shelter in Cambridge, and any remaining spots by the end are let-ins at the door, he says.

A Dominican woman stands at the front, dressed head to toe in black. With her hood pulled up and hand holding the lip of the zipper above her nose, her eyes are all that peek out. Shivering in the cold, she waits for the ticketed ones to pass her by. The line now seems pointless.

Soon, all the ticketed people have entered in ones and twos. Three remain. Another Bay Cove head peeks out from the warmth. It looks like we’re at capacity, says the employee at the door, but wait just a second, and we’ll check.

They don’t wait. In Spanish, the woman mutters something under her breath about discrimination, and in English, she thanks him for everything and says not to worry.

The three figures silhouette against the lights beaming out from the parking garage as they walk away. The employee emerges again, sees the disappearing wisps, and the quiet, calm man lets out a deep, long yell. “Wait!” It echoes down the walls of the alley. But not far enough.

His shoulders droop. “I told them to wait.”

Cover Photo: Backpacks line the sidewalk in front of the Boston Night Shelter, marking their owners’ places in the evening wait. (Credit: Shandra Back)

Massachusetts, the Only State with a “Right-to-Shelter” Law, Faces Increasing Demand for Services was first published by the Fulcrum, and republished as part of a partnership in best serving Hispanic, Latino communities.