For many families, Halloween opens the door to stories that go beyond pumpkins and witches — tales that spark wonder and curiosity.

Within Latino and Hispanic communities, this time of year invites the retelling of ancestral legends that echo with mystery, heritage, and emotional depth. Among the most haunting are La Llorona, El Silbón, and El Cadejo — folkloric figures whose chilling tales have been passed down for generations. But these aren’t just ghost stories. They are moral compasses and timeless reflections on grief, justice, and the choices that shape all of us.

La Llorona: The Weeping Woman of the River

La Llorona, or “The Crying Woman,” is perhaps the most iconic figure in Latin American folklore. Originating in Mexico, her story tells of a woman who drowned her children in a fit of rage or despair and now wanders riversides, eternally mourning their loss.

“La Llorona isn’t just a ghostly legend; she represents deeper themes of loss, regret, and the consequences of our actions,” wrote Jodie Lawrence in the article, What Does La Llorona Symbolize in the Context of Grief and Maternal Love.

Her cries — “¡Ay, mis hijos!” — are said to echo through the night, warning children to stay close to home and away from dangerous waters. In some versions, she appears in white, her face obscured, luring the curious toward peril.

In Searching for La Llorona, Norma Elia Cantú and Kathleen Alcalá write that in the Florentine Codex, an encyclopedic work on the Nahua peoples of Mexico completed during the 16th century by Aztec scribes working with the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, “we find two Aztec goddesses who could be precursors to La Llorona. The first is Ciuacoatl or Coatlicue, described by Sahagún as ‘a savage beast and an evil omen’ who ‘appeared in white’ and who would walk at night ‘weeping and wailing.’ The Aztecs considered her a snake-skirted mother figure and a warrior, patroness to women in childbirth. Ciuacoatl can also be linked to the sixth of ten omens recorded in the Florentine Codex as having foretold the arrival of the Europeans and the subsequent conquest: the voice of a woman crying about the fate of her children.”

The legend has inspired countless adaptations, including films, books, and even civic storytelling projects.

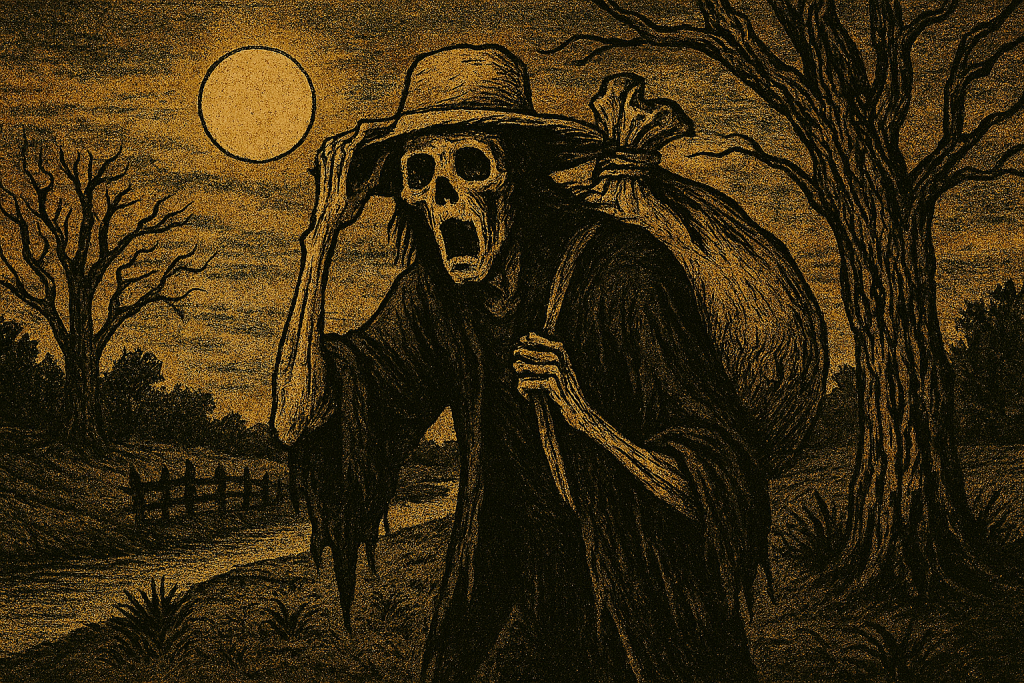

El Silbón: The Whistler of the Plains

From the Venezuelan and Colombian plains comes El Silbón, a spectral figure known for his eerie whistle — a tune that signals his proximity in reverse. If the whistle sounds far, he’s near. If it’s close, you’re safe… for now.

Per the USC Digital Folklore Archives, Venezuelan Ghost Stories Collection, “El Silbón is a ghost who carries a bag of bones, said to be his father’s, and he whistles a chilling tune that signals death.”

The tale warns against violence and excess, often told to young men as a moral compass. In some regions, families light candles or play music to ward him off during harvest season or Halloween.

In the column, El Silbón, a Venezuelan Legend About the Ancestors, Alan U. Dalul writes: Few things repel El Silbón, but the most popular protections are the barking of a dog, a whip, and the Lord’s Prayer, which is said to scare the specter in the act. Rereading the legend, one might think that alcohol could act as a defense, especially brandy.

El Cadejo: The Spirit Dogs of the Road

Central American folklore introduces El Cadejo, a pair of supernatural dogs — one white, one black — who follow travelers at night. The white Cadejo protects the innocent; the black one brings misfortune and madness.

“El Cadejo’s origins go back to a time before European colonization. Indigenous peoples in Central America believed in spirit animals, or nahuales, that acted as protectors or guides,” writes Dani Rhys. “When the Spanish arrived, they brought their own beliefs, and the Cadejo story grew into a blend of old and new ideas.”

In Guatemala and El Salvador, the legend is often shared during All Saints’ Day and Halloween, with families recounting encounters or dreams involving the dogs. Some even leave offerings at crossroads to honor the protective spirit.

Why These Legends Matter

These tales aren’t just spooky — they’re deeply symbolic. They reflect colonial trauma, gender roles, moral codes, and the power of storytelling in shaping identity.

For families seeking Halloween stories, these legends offer rich material for costumes, altars, and theatrical retellings. They also invite reflection: What are we afraid of? What do we protect? What do we pass down?

In many Latino communities, storytelling around Halloween is seen not just as entertainment, but as a way to teach children to listen, feel, and remember.