Don’t have time to read? Listen to the story instead.

For the first time, Entre Ríos Books is generating enough revenue to cover the publishing house’s costs, but its future is still uncertain.

The poetry press specializes in contemporary Argentine poetry, translations, and collaborations between poets and artists, with a focus on bilingual editions.

Yet, it faces the tough realities of the small press world: limited distribution channels, the high cost of quality translations, and the challenge of finding an audience willing to read translated poetry.

“Our initial mission was that our press was going to do two things: it was going to focus on Northwest writers, artists, and translators, and we were also going to publish books from Argentina,” said Knox Gardner, the publisher and editor-in-chief of Entre Ríos Books. “Publishing the work from Argentina would be a way for us to honor my husband’s heritage while also building new connections there. I did not understand how much more difficult the process of translation publishing would be.”

Gardner’s husband, Victor Chudnovsky, left Argentina when he was four after his parents fled a dictatorship.

The family moved to Venezuela before eventually moving to the United States. Chudnovsky, who works full-time, currently funds the press. But as Chudnovsky approaches retirement, the couple wonders how their beloved press will survive.

“I think our future will, by necessity, be smaller.” Gardner said. “Perhaps only one translation project a year, or perhaps we are going to only be doing chapbooks, small paperback booklets. It is a big unknown. Right now, a typical book for us costs about $8,000 for the entire process. It is hard to know what I am willing to cut. ”

Gardner explained that the sales numbers can be difficult to face when it comes to poetry in translation, especially if it’s the first translation of an author who is not widely known.

“I mean, the math of it is terrible,” Gardner said. “Out of the 300 to 400 we produce, only 100 might sell. The rest get traded, passed around, sent out for reviews. We do whatever we can to promote the author’s work even if in the end we give the books away.”

Entre Ríos Books is not alone in this experience.

Translations account for 3% of books published in English each year in the U.S., a lower percentage compared to countries like Germany, where around 50% of published books are translations.

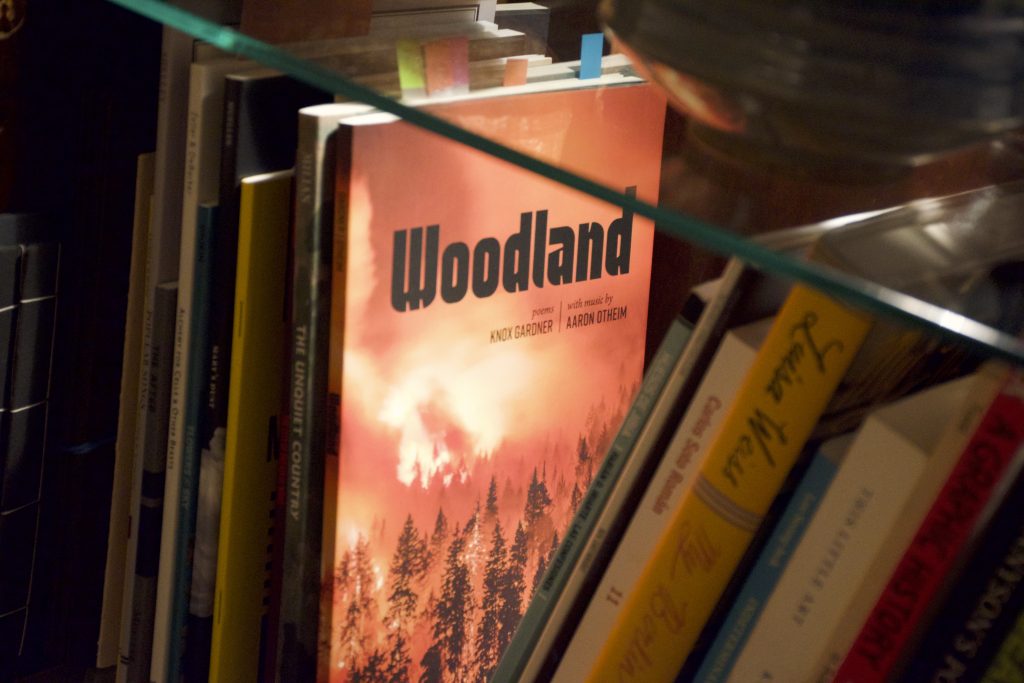

The front cover of the “Woodland,” a poetry collection by Knox Gardner, the publisher and editor-in-chief of Entre Ríos Books.

Photography: Emma Schwichtenberg

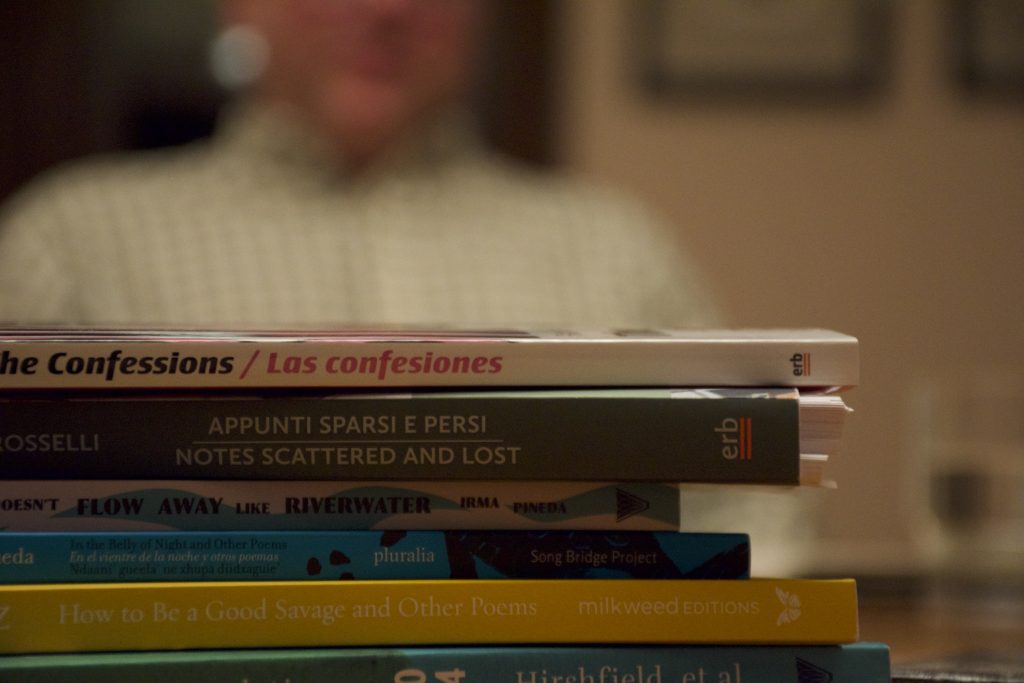

A collection of translated poetry.

Photography: Emma Schwichtenberg

Gabriela Adamo, a translator and editor based in Buenos Aires, Argentina, explains that the low number of translations into English has been a problem, particularly for Latin American literature, which has been neglected in the global market.

“Smaller presses are the ones who are really championing translation in the U.S.,” Adamo said. “The big publishing houses go for the safe bets. They will translate an author only when they are sure that author will sell. So, they are not really betting on the most interesting authors from Latin America, and the same happens with other languages.”

Smaller publishing companies, like Entre Ríos Books, face the challenge of bringing these works to the U.S. market. However, as larger publishing houses anticipated, finding readers for translated poetry remains a considerable hurdle.

“I think the biggest challenge I have is just finding our curious readers,” Gardner said. “Where are they? Where are the people who are interested in poetry and, actually, willing to spend money on it—in translation, in bilingual editions?”

Wendy Call is a literary translator and series co-editor for the annual Best Literary Translations series.

In 2022, a book she translated, “In the Belly of Night and Other Poems,” by Irma Pineda, was co-published by U.S. and Mexican publishers.

“I did not understand when I started how hard it was going to be to interest U.S. publishers in Indigenous Latin American authors,” Call said. “And also how almost impossible, but not quite impossible, it was going to be to get a U.S. publisher interested in perhaps publishing a trilingual book, because it is an order of magnitude more complicated than a bilingual book.”

“In the Belly of Night and Other Poems” is a trilingual poetry collection translated from Isthmus Zapotec into Spanish and then again into English by Call.

While working with the Mexican publisher of “In the Belly of Night and Other Poems,” Call served as an interpreter.

When the Mexican press asked how many copies the U.S. wanted, Call replied that they could probably sell 300.

“The Mexican publisher looked stunned, as they typically print 1,000 to 1,500 copies,” Call said. “Considering the U.S. has three times the population of Mexico, they expected a larger order. So, when the U.S. press said they only wanted a fifth of that number, it really highlighted the difference in demand for poetry between the two countries.”

According to Gardner, small presses often struggle to reach readers, as distribution remains a persistent obstacle.

“The fundamental problem for any small press is getting the book you’ve created into a bookshop and having it displayed where someone can see it. That’s the number one challenge,” Gardner said. “And this issue is compounded when it’s a translation. I mean, there’s a pecking order of books. If you have a novel, then you’re in better shape.”

He didn’t miss the irony that Entre Ríos’ best-selling poetry collection resembles a novel.

“It’s a great, big, thick thing, and so, you know, you pay attention to what you’ve done, and you’re like, Yeah, novels are where it’s at. Man, maybe we should be doing a novel now and again,” Gardner said.

According to Call, Argentina, Mexico, and Chile are the countries with the most translated literature from Latin America.

Argentina and Mexico are ahead of other Latin American countries largely due to their larger publishing industries and strong literary cultures, Call said.

“It’s fascinating to see the interest and enthusiasm for literature in Mexico, especially poetry,” Gardner said. “In the U.S., however, it seems harder to generate the same level of engagement—perhaps because our cultural landscape is more fragmented or simply because there’s less widespread interest in poetry as a form of expression.”

Both countries have invested significant resources, particularly through their governments, to promote their literature internationally, especially in English.

“They mostly focus on prose because they know that fiction and even essays will sell more in the U.S. than poetry. But both countries have done a lot in the last quarter century,” Call said.

Programa Sur is an Argentine government grant program that supports the translation of Argentine literature into foreign languages.

The grant can be up to three thousand two hundred dollars per work, according to their website.

“I think small presses do need help from governmental offices or some kind of foundations to be able to pay for translations,” Adamo said. “Translations are more expensive because you need to pay for the translators.”

Call works closely with authors when translating their books.

“There’s a huge amount of research that goes into it, and I only work with writers who are willing to spend that time with me, which is a big ask,” Call said. “Many translators do not work that way.”

In cases where she cannot directly consult the author, she relies on language teachers and other resources to resolve uncertainties when translating works originally created in Indigenous languages, rather than in Spanish.

This collaborative approach is key to her translation process.

“Whenever you’re working with someone’s artistic product, and particularly as a non-Indigenous person translating Indigenous Latin American authors and putting them out to a general U.S. market,” Call said. “We have to be really careful that we’re not misrepresenting their work or exploiting them.”

As an independent press, Entre Ríos Books has the opportunity to build closer relationships with its authors, and one way this is reflected is through the covers Gardner helps create for each poetry collection.

“I want our poets to agree that the book looks how they envisioned it should look, or how they want their work presented in the best way possible,” Gardner said. “Each book has its own unique universe. For all our Argentine translations, we have been hiring Argentine artists to do the covers and the art inside, and poets have recommended these different artists.”

To Adamo, the situation surrounding Latin American translations is very complex.

She notes the large Latino population’s specific interest in Latin American literature, but it’s unclear whether they would prefer to read books in Spanish or translated into English.

“I really think there will be a growing interest from this population in reading translated fiction, even from Spanish, because first- and second-generation individuals are losing their Spanish very quickly,” Adamo said. “They might speak it at home, but they feel much more comfortable reading in English.”

Four books remain under contract at Entre Ríos Books, two of which are scheduled for release in January.

“I think our future looks like incredibly small, real runs of a gorgeous book, and then going to print on demand,” Gardner said. “I mean, you know, you still do it because you love it, yeah, so, you know, there’s no positive spin. It’s brutal, but I love it.”

You can find Entre Ríos Books online at entreriosbooks.com.