In a modern house nestled in the mountains along the border with Lebanon, the aroma of pitas with zaatar (flatbread with herbs) and cheese mixes with the inspiring

voice of Neveen Elías. As she prepares lunch, she also checks messages from her fellow reservists in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). A soldier, community spokesperson, and Maronite Christian, Elías embodies the complex life of Arameans in Israel — an almost forgotten minority that still speaks Aramaic, the language Jesus of Nazareth spoke.

“We want to build the first Aramean village here in Galilee,” she says. “We don’t need money. We need people in the United States to speak with the government, to ask them to support us, to help us build the first Christian Aramean village in Galilee.”

Aramaic was, for centuries, the dominant language in the Middle East and the language Jesus spoke. Its decline began in the 8th century with the Arab expansion, which established Arabic as the primary language. Today, it is estimated that only about half a million people speak Aramaic worldwide, compared to more than 400 million who use Arabic.

In Israel, Arameans are part of the Maronite Church, founded in the 4th century by Saint Maron in Syria. Only about 10,000 Maronites live in the country, spread across Galilee, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem. For them, preserving the language means preserving their faith.

There are tens of thousands of people with Latin American ties in Israel, including over 100,000 Jewish immigrants and their descendants, primarily from Argentina, plus thousands of non-Jewish workers (mostly undocumented) from Ecuador, Colombia, and elsewhere. Around 180,000 to 188,000 Christians live in Israel, making up roughly 1.9% of the population.

Israel, a country smaller than states like North Carolina or New York, contains a unique religious diversity: about seven million Jews, nearly two million Arab Muslims, and small Christian communities such as the Arameans. For the Maronites, cultural survival depends on passing the language and traditions to new generations, since most of those who still speak Aramaic are elderly.

Elías found in the Israeli Christian Aramaic Association (ICAA), where she has been a member for nine years, a space to carry out that mission. From there, she organizes camps and workshops to promote the Aramaic language.

“During the camp we teach the children our culture, our language, our identity, and our history because these are not things they learn in school,” she says.

In addition, the ICAA maintains ties with Aramean communities in other countries to uphold a united front in defense of their identity.

Elías insists that integration is possible. Every year, she participates in a program where 45 young people — half Jewish and half Christian — live together for seven months in the Beth Zera kibbutz, on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. There, they share prayers, holidays, and experiences before beginning their military service. “We celebrate Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles) with the Jews, and we also celebrate Christmas and Hanukkah together. That’s how we learn to understand one another,” she says.

She adds that living together is not just an ideal, but a necessity.

“We live with Muslims, Bedouins… Jews… We try to understand how to live together in peace and make room for everyone; we just need everyone to understand and take care of one another,” Elías said.

The relationship between the Arameans and the State of Israel, however, is complex. Elías, an IDF reservist and the mother of a son who also serves in the army, describes her community’s support for the soldiers. “I see that the people here and our community help the IDF a lot. For example, they (the community) don’t argue with the IDF when they use our village to stay or to fight against Hezbollah… The people in our community take care of the soldiers, they support them.”

She also acknowledges that there is skepticism within the community, which she attributes to Operation Hiram, carried out in November 1948, when the Arameans of her village were evacuated by the Israeli army. This IDF operation sought to eliminate Arab resistance within Galilee.

“They left, but they made a promise — the Jewish promise, the government’s promise, and the promise of our patriarch — that we would be allowed to return once the situation calmed down, but it never happened.” Elías said her community has not forgotten the actions of the IDF.

She said that in 1953 the Supreme Court allowed her ancestors to return, but they found their homes completely destroyed.

That historical wound fuels mistrust, although Elías insists that integration is possible: “It is possible to be involved and to integrate into our country.” Israel was the first country in the Middle East to recognize the Aramean identity.

“We hear from our families in Lebanon about how they live. We hear from Jordan and Syria… Christians suffer a lot.”

In contrast, she points to Saudi Arabia — where laws prohibit the public practice of Christianity — as an example of persecution in the region.

As she balances her life between family, the IDF, and her community work, Elías always returns to the same compass: her faith.

“I want [Americans] to know that the Arameans, the Aramaic language, and the language of Jesus… are still alive.”

Preserving Aramaic: One Woman’s Fight to Save the Language of Jesus was first published in Spanish language as Mujer lucha por mantener viva la lengua original de Jesús: el arameo on La Noticia and re-published in English with permission.

Esteban Balta is a student at Northwestern University. He was a fellow with Fuente Latina, an organization that sponsors journalists and students to visit Israel. Esteban is the son of Hugo Balta, executive editor of the Fulcrum and publisher of the Latino News Network.

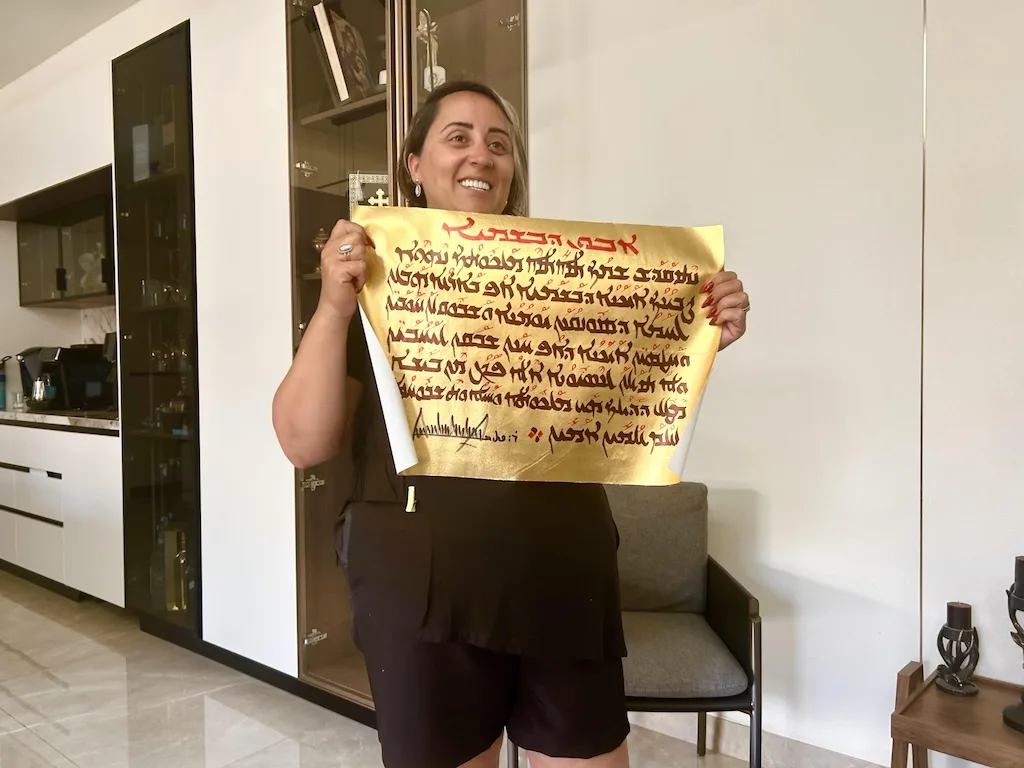

Cover Photo: Naveen Elías shows a prayer in Aramaic that a priest gave her. Credit: Esteban Balta.