OLYMPIA — Aidé Villalobos starts her mornings by greeting third graders in Spanish as they walk into her classroom.

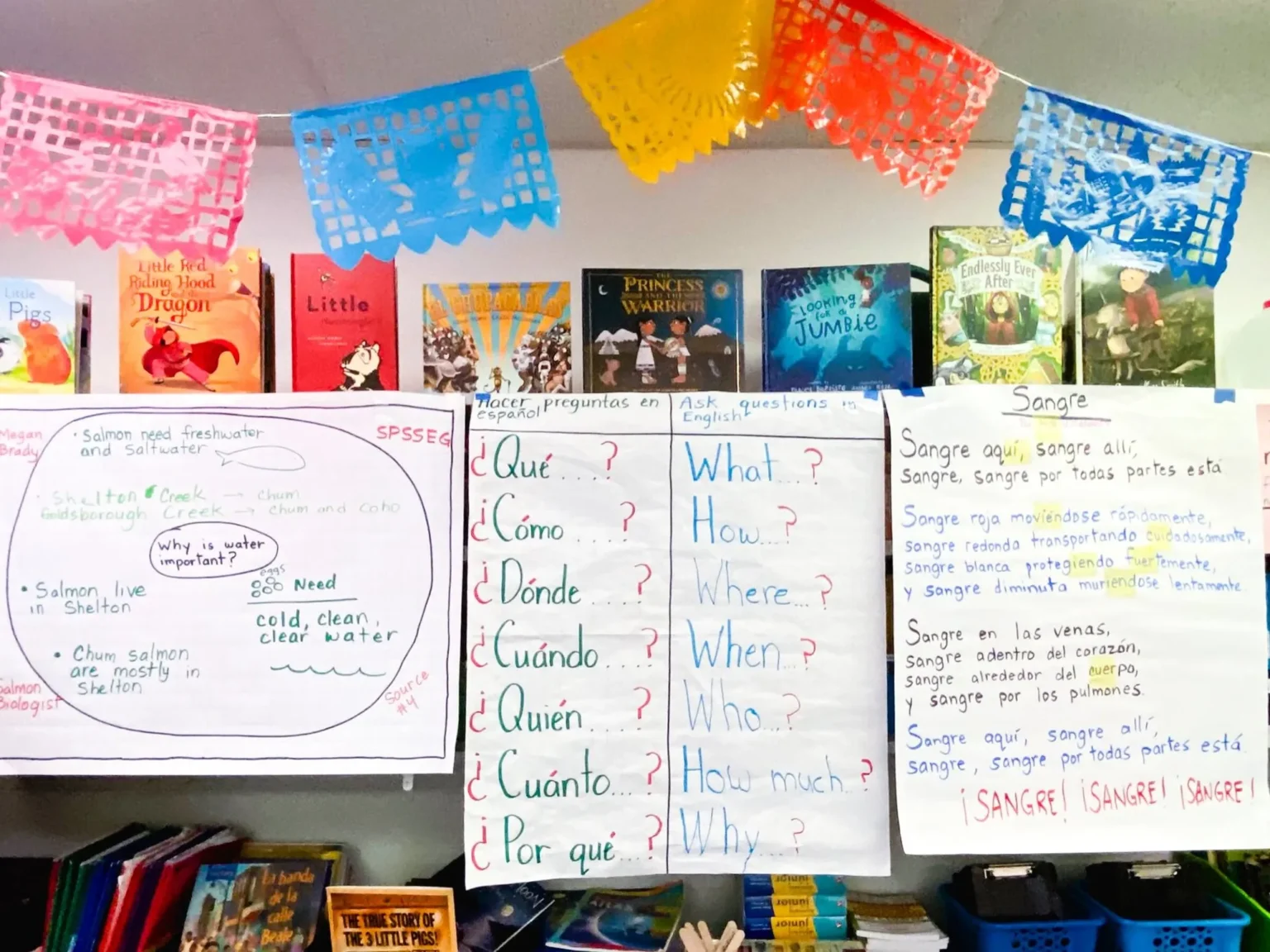

Posters on the walls are in Spanish and English, helping students practice multiplication tables, read poems, sing songs and do science experiments in both languages.

Dual language programs, like the one Villalobos teaches in rural Mason County, provide Washington’s K-5 students the opportunity to learn core subjects in English and a second language, with many students becoming fluent in both by the time they leave elementary school.

Educators say that to sustain and expand dual language and tribal education, increased funding is needed. House Bill 1228, sponsored by Rep. Lillian Ortiz-Self, D-Mukilteo, passed unanimously in both the House and Senate. It would create permanent funding to make these programs available to every school district by 2040.

“In the United States, we’ve been so monolingual, and we’re missing that brain development piece that is so enhancing for our students,” Ortiz-Self said. “We want all our students to have those opportunities.”

The Legislature plans to annually fund at least 10 new dual language education programs, with the average grant award of $40,000. Those grants will help with program startup costs, support professional development for teachers and provide instructional materials in the second language being taught.

Currently, 141 schools offer dual language programming, with 122 of those schools teaching Spanish.

Dual language programs are taught differently depending on the school or district. Some start off teaching kindergartners in one language for 90% of the day and increase English by 10% every year until both languages reach 50%.

In other programs, like the one Villalobos teaches, kids spend 50% of their day learning in Spanish and 50% learning in English.

Villalobos uses pictures, videos, drawings, diagrams and lots of hands-on experiences to teach English Language Learners and students who grew up speaking English simultaneously. She also uses group work and places students in pairs to develop their language skills.

“They’re starting to understand we don’t exist in one language at a time,” Villalobos said. “When we’re bilingual or trilingual, our brain is always working, and we’re able to use whatever language we can express ourselves in.”

Dual language education is a long-term investment, said Radu Smintina, education policy manager at OneAmerica, an immigrant rights organization. It takes students five to six years to become literate in two languages.

Data from 2023 shows test scores have yet to catch up to pre-pandemic levels with the biggest improvements coming from younger grades. Expanding dual language education could improve overall test scores, Ortiz-Self said.

Once students reach that level of fluency, both ELL students and native English speakers outperformed students in mainstream English programs in both English and math standardized test scores, according to a 2016 study in the National Library of Medicine.

Additionally, students in dual language programs are exposed to multiple languages and cultures as early as kindergarten.

“Being exposed to different cultures early on — that’s also huge in my perspective, especially when we look at how divided our country currently is,” Smintina said.

These programs will also help ELLs, who come to the United States without knowing English, transition into classrooms. According to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, there are over 146,000 ELL students in Washington, with many falling behind.

The percentage of students making progress toward proficiency in English has fallen from 67% in 2016 to 36% in 2023, according to data from OSPI.

Traditional ELL programs focus on just teaching students English and isolate them from their peers, which often leaves them falling behind in other subject areas, Ortiz-Self said. But dual language programs allow students to learn English alongside students learning a new language.

The bill also intends to expand tribal language education, which allows Indigenous students to reconnect with their language, culture and oral tribal traditions in schools.

“It’s about identity for a lot of us, to hold on to our roots and not forget where we come from,” Villalobos said.

Since 2015, the Legislature has provided funding for grants to build and expand dual language programs in schools. Having permanent funding will allow these programs to be more accessible to students across the state and better support educators.

“Oftentimes, we have to work harder to find the materials,” Villalobos said. “I have to work a lot more to find materials in Spanish and either create it or I have to buy it.”

This bill would allow districts to apply for funding through OSPI to start or expand current dual language or tribal education programs. Schools with over 50% students of color will be prioritized.

The bill is awaiting Gov. Jay Inslee’s signature to become law.

“If we truly want equity for all of our students, we need to provide dual language opportunities for every one of our students who needs it,” Villalobos said.

Cover Photo: Posters in Spanish and English hang on the walls of Aidé Villalobos’, a dual language educator, classroom. Programs like this provide Washington’s K-5 students the opportunity to learn core subjects in English and a second language, with many students becoming fluent in both by the time they leave elementary school. (Courtesy of Aidé Villalobos)

Publisher’s Notes: Jacquelyn Jimenez Romero, a final-year student at the University of Washington, is an intern with WA Latino News (WALN).

Dual language education is one step closer to becoming a WA law was originally published in The Seattle Times, and was republished with permission.

Part of LNN’s mission is to amplify the work of others in providing greater visibility and voice to Hispanic, Latino communities.