In the past year, Chicago has made international news as asylum seekers from Ukraine and Venezuela desperately seek refuge in the Windy City. More recently, the press has rightfully covered the dishearteningly unequal treatment received by these two groups of migrants.

Such stories from Chicago remind us that migration is inherently political in character, injustices among diasporic communities are real, and representation itself often informs a group’s well-being.

Given these latest headlines, a current exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art feels particularly timely. Titled entre horizontes: Art and Activism Between Chicago and Puerto Rico, the survey show features 17 artists, each of whom maintain a relationship with both Chicago and Puerto Rico.

Having opened in August 2023, entre horizontes—best translated as “between horizons”—will run through May 5, 2024. Curated by Carla Acevedo-Yates, the ambitious exhibition features an “intergenerational group of artists with ties to Chicago” who work in different media—paintings, films, and a few installation pieces. Furthermore, the exhibition showcases paraphernalia from Puerto Rican activists operating in Chicago during the 1960s and 1970s.

The most compelling pieces included in the show combine the aesthetic and the political, as well as those that point up the shared trajectories of social justice in Chicago and Puerto Rico. Indeed, rendering the show’s title in lower-case letters—entre horizontes rather than “Entre Horizontes”—aptly captures the exhibition’s guiding conceit: to collapse hierarchies and sidestep any sense of capitalized place names.

Due to Puerto Rico’s unique relationship with the United States—technically defined as an “unincorporated territory”—entre horizontes speaks to both the pain and joy of belonging to a community without clear national horizons. Today, the Puerto Rican diaspora is routinely conceptualized as a community in limbo, perpetually in transit between the U.S. Mainland and a diminutive island in the Antilles via a “flying bus.”

Entre horizontes follows soon after two other U.S. art shows highlighting the Caribbean and, more specifically, Puerto Rico. Between 2022 and 2023, New York City’s Whitney Museum of Modern Art displayed no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria, while another show curated by Acevedo-Yates titled Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990s–Today was put on at Chicago’s MCA and is currently at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. In many ways, Acevedo-Yates’ shrewd vision of the Puerto Rican diaspora—its people, its art, and its politics—is deepened and clarified with entre horizontes.

This is especially opportune given Chicago’s recent interest in preserving the histories, promoting entrepreneurship, and officializing the monuments of the city’s Puerto Rican community. Chicago, a profoundly polyglot city, also speaks boricua. The exhibit benefits greatly from Acevedo-Yates’ due diligence in the political history of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community. She rightly notes that it was in Chicago where José “Cha Cha” Jiménez founded the Young Lords Organization, a street gang that transformed itself into an anti-colonial activist group, and whose social justice initiatives aimed to help the Puerto Rican community in neighborhoods like West Park, Lincoln Park, and Humboldt Park even while advocating for Puerto Rican independence from afar. The history of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community is extensive, rich, and defined largely by struggle: the city witnessed the Division Street Riots of 1966, the 1980 arrest of members of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN), and the 1993 kerfuffle surrounding a statue dedicated social activist Pedro Albizu Campos.

Acevedo-Yates astutely places paraphernalia surrounding these disparate but relate political events squarely in the center of the MCA’s Sylvia Neil and Daniel Fischel Galleries.

Frank Espada’s NEH-financed street photographs of hardscrabble yet sanguine Puerto Ricans hang across the back wall—figures that are a testament to Puerto Rican history (fig. 1).

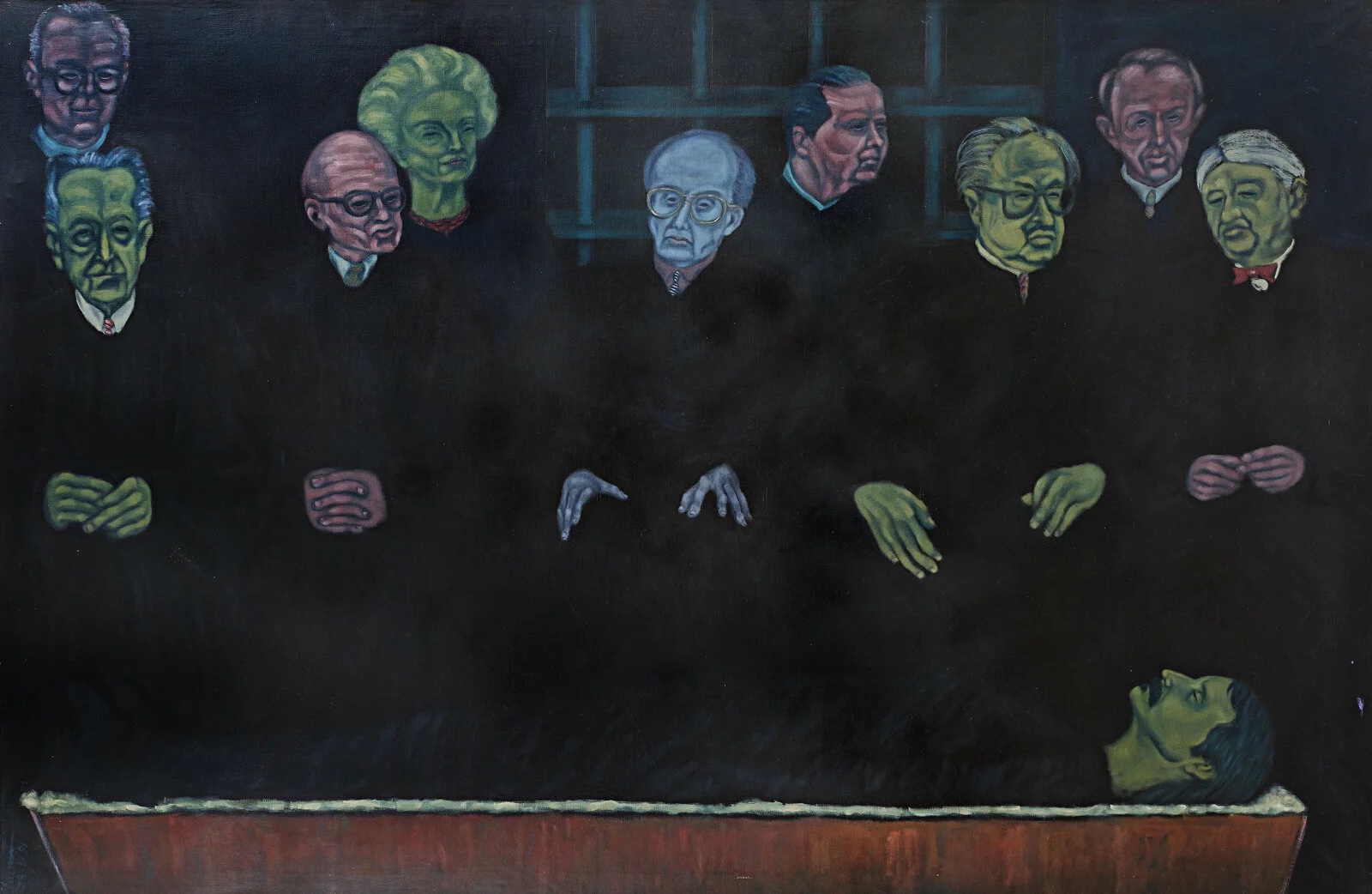

Another highlight of the show is a La ficción, a 1989 oil painting by political prisoner Elizam Escobar, a member of the FALN dedicated to Puerto Rico’s independence, and who was eventually sentenced to 68 years for seditious conspiracy (fig. 2). Rendered in tenebrous and ghoulish hues, the painting depicts the nine United States Supreme Court justices, poised unperturbed over Escobar’s dead body.

Escobar would later refer to his time spent in federal prison as experiencing a type of “living death.” Perhaps like Puerto Rico itself, a locale situated in the half-lights of nationhood, Escobar, too, finds himself in limbo.

These explicitly political interventions are judiciously tempered throughout the gallery with more aestheticized pieces that still serve to underscore the rich peculiarity of the Puerto Rican diaspora in Chicago and beyond.

A case in point is Arnaldo Roche Rabell’s Aquí y allá from 1989 (fig. 3). The work portrays four shadowy, abstract, and faceless human subjects rendered in painterly strokes and backgrounded by Chicago’s brawny, immediately recognizable skyline.

The allegorical piece feels reminiscent of a danse macabre: the tense, eerie bodies in motion express both the ecstasy of arrival on the shores of Lake Michigan and the beautiful struggle for survival which is the American Dream. Aquí y allá, like Pedro Pietri’s celebrated poem “Puerto Rican Obituary” articulates a people’s ambiguous relationship to life in the U.S. According to the accompanying museum label, Roche Rabell created the work by placing “a paint-covered canvas over a model’s body and vigorously rubbed the resulting contours.” Thus, unlike Yves Klein’s mid-century attempts to integrate models, paints, and performance—works that suggested the esoteric spiritualism of a human race ready to atomize itself—Roche Rabell’s painting underscores the corporeality and humanity at the heart of issues all too often reified: nationalism, migration, and labor.

The cleverest, most striking but also, subtlest piece in the show floats high above the gallery, hanging from the ceiling. There, we find Edra Soto’s Tropicalamerican, a set of four flags whose designs are familiar to the eye, yet are uncannily rendered in earthy green tones (fig. 4). The reworked U.S. and Puerto Rican flags were crafted by digitally photographing real, tropical leaves that had originally been quilted together. From below, Soto’s work beautifully mimics the look of undulating fabric. Although Soto’s professional website proposes the work of Jasper Johns as a point of reference, given the context of the MCA show, it is difficult not to register Tropicalamerican as influenced by Puerto Rico’s remarkably playful and political relationship with its own flag. The flag, as a foremost emblem of nationhood, takes on a unique salience for Puerto Rico—this nation without a state. Indeed, Puerto Rico’s paradoxical place vis-a-vis the community of nations is well-known.

Thus although the island has representatives in D.C., their voting power is significantly limited; moreover, those on the island pay Social Security yet enjoy fewer federal benefits. These are but a few of the many contradictory elements.

In the absence of complete sovereignty, Puerto Rican energies often focus on their (aesthetic) symbols of nationhood—paramount among these, is the flag itself. Thus, while the mid-century saw the Puerto Rican flag banned to quell the independence campaign, today “Que bonita bandera”—that is, “What a Beautiful Flag”—is the movement’s unofficial anthem.

The Puerto Rican flag is paraded up and down the streets of New York City’s Fifth Avenue, is included on the uniforms worn by the commonwealth’s own Olympic team, and becomes an emblem of resistance when cast in black and white.

Seen in this context, Soto’s Tropicalamerican playfully challenges received national ideologies; the flags’ verdant tones suggest that people and places may be better organized according to affect and environment, rather than abstract, governmental objectives.

Although social critics have rightfully interrogated whether the discussion of statehood, Puerto Rico’s cultural nationhood, or even pop stars can catalyze worthwhile political change on the island and beyond, Acevedo-Yates’ exhibit proposes that politics, too, is an art.

Even as Chicago bureaucrats decide the place of Latinx migrants in the city, entre horizontes reminds us that these same communities have consistently crafted their own stories with style, grace, and art. Let’s hope they continue the beautiful struggle.

Cover Photo: Elizam Escobar (b. 1948, Ponce, Puerto Rico; d. 2021, San Juan, Puerto Rico), La Ficción, 1989. Oil over acrylic on canvas; framed. Private Collection, Puerto Rico. Photo: John Betancourt.

Originally from Chicago, Dr. Kevin M. Anzzolin is a Lecturer of Spanish at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. Besides teaching a range of courses in Spanish and English, his monograph, Guardians of Discourse: Literature and Journalism in Porfirian Mexico, is slated to be published with the University of Nebraska Press in 2024. Both his scholarship and his public-facing pieces can be found here.

Publisher’s Notes: Do you have an idea for an Opinion Editorial or Review? We want to hear from you! Send us submissions to info@LatinoNewsNetwork.com